📊 Piecewise Rejection Sampling

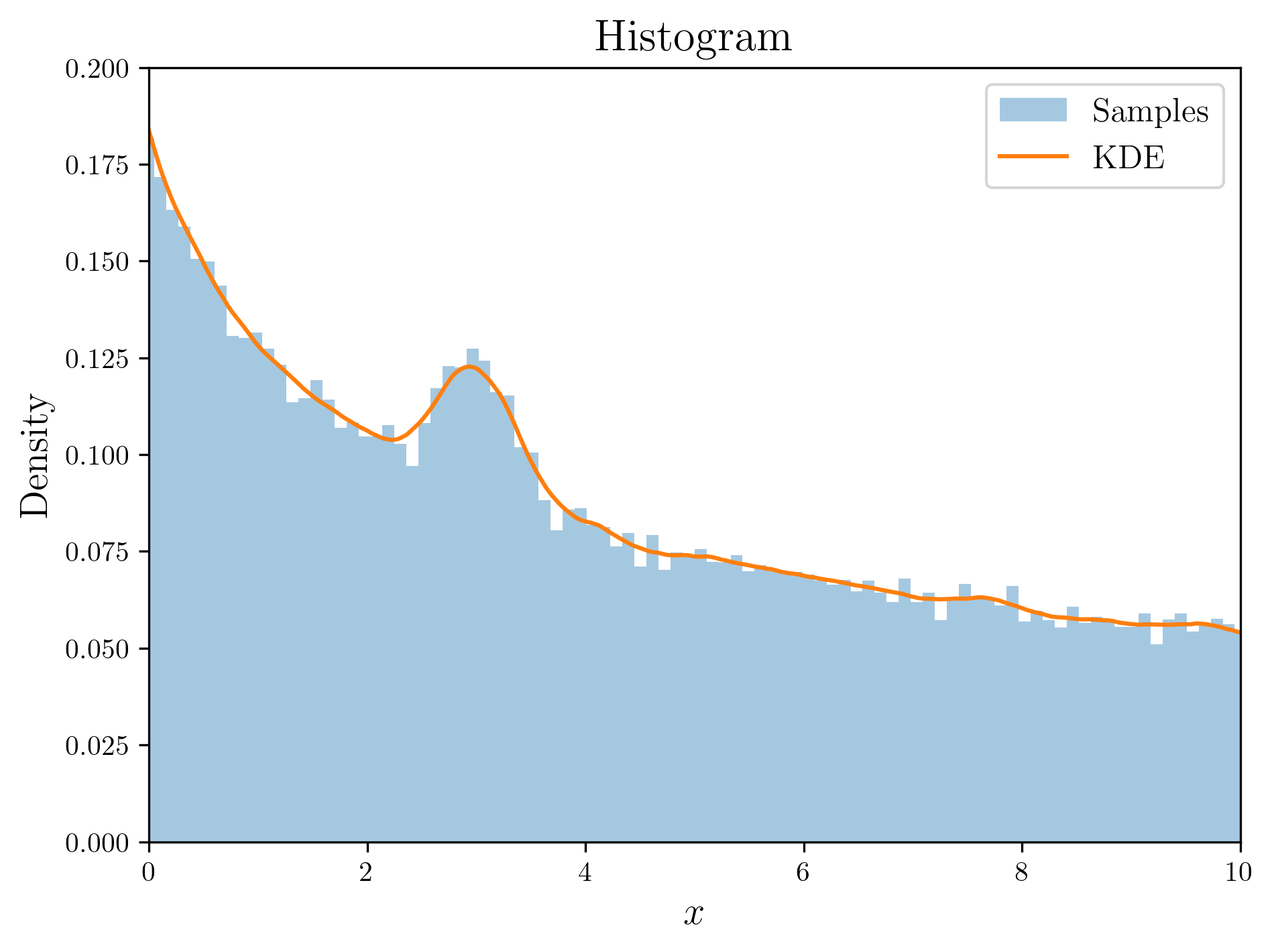

![Differential energy spectrum of ALPs from primordial black hole (PBH)${}^{[1]}$](/posts/images/006_01_test_dist.png)

Differential energy spectrum of ALPs from primordial black hole (PBH)${}^{[1]}$

Suppose you’re presented with an unnormalized probability density function graph such as the one shown. If you’re tasked with generating 10,000 data points that conform to this distribution, what would be your approach?

Here are the two most commonly used methods to sample data from an arbitrary probability density function:

Inverse Transform Sampling involves generating data points by calculating the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the probability density function, deriving its inverse function, and then using this inverse function to produce data points. This method can be quite efficient, but if the exact form of the probability density function is unknown—as in our case—it becomes challenging to apply${}^{[2]}$. On the other hand, Rejection Sampling is versatile and can be utilized regardless of the probability density function’s form. Therefore, we’ll begin with Rejection Sampling.

1. Rejection Sampling

Rejection sampling , a.k.a. the acceptance-rejection method, employs a straightforward algorithm. To describe it, let’s represent the target probability density function as $f(x)$. When direct sampling from $f(x)$ is not feasible, we introduce an auxiliary function $g(x)$, which is easy to sample from. For a chosen positive constant $M$, it’s required that $f(x) \leq M \cdot g(x)$ across the domain of $x$. This relationship is depicted in the figure below:

A graph commonly seen in particle physics

Typically, the uniform distribution is the simplest to sample from, so we define $g(x)$ as $\text{Unif}(x|0,10)$. Given that the peak value of $f(x)$ is 1, we select $M=10$ to ensure that $M \times g(x)$ consistently surpasses or meets $f(x)$. The sampling process using this graph is as follows:

-

Draw a sample $y$ from $g(x)$, which in our case would be a value from $\text{Unif}(x|0,10)$.

-

For the chosen $y$, draw a sample $u$ from $\text{Unif}(u|0,M \cdot g(y))$. This step always utilizes a uniform distribution, regardless of $g(x)$’s configuration.

-

If $u$ is less than or equal to $f(y)$, then $y$ is accepted as a sampled value from the desired distribution $f(x)$. If not, the process is repeated from step 1.

This method is named ‘rejection sampling’ because samples where $u > f(y)$ are discarded. By following this algorithm, we can simulate sampling from the desired probability distribution $f(x)$. To implement this, we will explore the cumulative probability distribution function (CDF).

If we denote the random variable $X$ obtained by Rejection sampling, we can establish the following relationship for two other random variables $Y \sim g(y)$, $U \sim \text{Unif}(u|0, M\cdot g(y))$: $$ P(X \leq x) = P\left(Y \leq x \,|\, U < f(Y)\right) $$ The conditional probability on the right-hand side represents the probability that $Y$ is less than $x$ when $U$ is not rejected, which is like step 3 in the algorithm above. Using the definition of conditional probability, we can transform this into: $$ P(X \leq x) = \frac{P (Y \leq x,~U < f(Y))}{P(U < f(Y))} $$ First, let’s expand the numerator using the probability density function: $$ \begin{aligned} P(Y \leq x,U < f(Y)) &= \int P(Y \leq x,U < f(Y) | Y = y) \cdot g(y) \,dy \\ &= \int P(y \leq x,~U < f(y)) \cdot g(y) \,dy \\ &= \int 𝟙_{y \leq x} \cdot P(U < f(y))\cdot g(y) \, dy \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^x P(U < f(y)) \cdot g(y) \, dy \end{aligned} $$ When moving from the second to the third equation, we use the condition that $y \leq x$ and $U < f(y)$ are independent. Now, since $U \sim \text{Unif}(u|0,,M\cdot g(y))$, by substituting $\displaystyle P(U < f(y)) = \frac{1}{M\cdot g(y)} \times (f(y) - 0)$ we get: $$ \begin{aligned} P(Y \leq x,~U < f(Y)) &= \int_{-\infty}^x \frac{f(y)}{M\cdot g(y)}\cdot g(y) \, dy \\ &= \frac{1}{M} \int_{-\infty}^x f(y) \, dy \end{aligned} $$

Now let’s find the denominator: $$ \begin{aligned} P(U < f(Y)) &= \int P(U < f(y)) \cdot g(y) \, dy \\ &= \int \frac{f(y)}{M\cdot g(y)} \cdot g(y) \, dy \\ &= \frac{1}{M} \int f(y) \, dy \\ &= \frac{1}{M} \end{aligned} $$ Finally, by dividing the numerator by the denominator, we get: $$ P(X \leq x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f(y) \, dy $$ This is the cumulative distribution function of $f(x)$. Thus, we can conclude that the probability density function of the random variable $X$ obtained by Rejection sampling is $f(x)$.

Now that the mathematical proof is complete, let’s write some code to see if this actually works well in practice.

// Rust

use peroxide::fuga::*;

const M: f64 = 10.0;

const N: usize = 100_000;

fn main() {

// Create g(x)=Unif(x|0,10) & h(y)=Unif(y|0,M)

let g = Uniform(0.0, 10.0);

let h = Uniform(0.0, M);

// Rejection sampling

let mut x_vec = vec![0f64; N];

let mut i = 0usize;

while i < N {

let x = g.sample(1)[0];

let y = h.sample(1)[0];

if y <= f(x) { // Accept

x_vec[i] = x;

i += 1;

} else { // Reject

continue;

}

}

// ...

}

// Test function

fn f(x: f64) -> f64 {

1f64 / (x+1f64).sqrt() + 0.2 * (-(x-3f64).powi(2) / 0.2).exp()

}

The algorithm itself is simple, so the code is very straightforward. However, despite that, the results are impressive.

Result of rejection sampling

Rejection sampling is not limited by the form of the probability density function and is easy to implement, but it has a critical downside: computational inefficiency. To secure a sample in Rejection sampling, it must survive the rejection condition. This means that the higher the $P(U < f(Y))$, the faster samples can be obtained, and conversely, the lower it is, the longer it takes to secure a sufficient number of samples. This is known as the Acceptance rate , which we already calculated in the proof above.

Acceptance rate

In the algorithm we used, this is equivalent to $1/M$, which is like dividing the area occupied by $f(x)$ by the total area occupied by $M \cdot g(x)$. Therefore, the larger the difference between the distributions, the lower the Acceptance rate, and the longer it takes to secure samples. Our example exhibits a minor discrepancy between $g(x)$ and $f(x)$, which is manageable. However if the probability distribution has a significant number of zeroes, as we gave at the beginning, and we use a uniform distribution for $g(x)$, the majority of samples will be rejected. This not only increases the time required for sampling but may also render it virtually impossible to sample effectively from areas where the probability density is close to zero, such as the distribution’s tails. To circumvent this issue, we must seek more efficient methods that can improve the acceptance rate for distributions with extensive zero-value regions.

2. Piecewise Rejection Sampling

Indeed, the scientific community has developed several techniques to improve upon the basic rejection sampling method. Among these, Adaptive Rejection Sampling (ARS) stands out for its efficiency, though it operates under the assumption that the target function is log-concave. On the other hand, Adaptive Rejection Metropolis Sampling (ARMS) addresses the limitations of ARS by not requiring the log-concavity condition, making it more generalizable, but at the cost of being more complex to implement. While there are comprehensive R packages available that facilitate the use of these methods, there is a simpler alternative that I would like to present: Piecewise Rejection Sampling (PRS) .

PRS was developed as a direct response to a challenge I faced during my physics research. It retains the core principles of rejection sampling but proposes a more tailored approach for the auxiliary function $g(x)$. Rather than employing a simple uniform distribution, PRS uses a Weighted uniform distribution that is specifically optimized for $f(x)$. Let’s delve into this method step by step.

2.1. Max-Pooling

If you have an interest in deep learning, you might already be acquainted with the term Max Pooling . Max Pooling is a common operation in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and it is conceptually straightforward. Let’s proceed to the mathematical definition of Max Pooling to understand how it works.

Max pooling

Let $f\,:\,[a,b]\to \mathbb{R}$ be a continuous function and consider the equidistant partition of the interval $[a,b]$ $$ a = x_0 < x_1 < \cdots < x_{n-1} < x_n = b $$ The partitions size, $(b-a)/n$ is called stride. Denote by $\displaystyle M_i = \max_{[x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x)$ and consider the simple function

$$ S_n(x) = \sum_{i=1}^n M_i 𝟙_{[x_{i-1},x_i)}(x). $$

The process of approximating the function $f(x)$ by the simple function $S_n(x)$ is called max-pooling.

A simple function, in the context of measure theory, is one that assumes a finite number of constant values, each within a specific interval. For an in-depth explanation, you can refer to Definition 10 and Property 1 in the resource Precise Machine Learning with Rust.

In essence, Max Pooling is a process that yields a simple function from measure theory, which is defined by distinct constant values on various intervals. Specifically, when applied to a function $f(x)$, Max Pooling divides the domain into $n$ bins and within each bin, it identifies the maximum value of $f(x)$. These maximum values are then used as the constant, representative values for their respective intervals, thereby transforming $f(x)$ into a simple function with a finite number of plateaus corresponding to the local maxima within each bin. When we apply this concept to our initial distribution, we can observe the following:

Max-pooling for Test Distribution

The solid red line depicted in the figure represents the function $f(x)$, and the dashed blue line illustrates the outcome of applying Max Pooling to $f(x)$. Astute observers might have realized by now that this blue line will serve as $M\cdot g(x)$ in our rejection sampling process. To implement this, we will establish a probability distribution that resembles a uniform distribution within each interval but differs in terms of the representative values. This forms the basis for the Weighted uniform distribution —the optimized $g(x)$ that we’ve referenced earlier—which adapts the uniformity concept to accommodate varying weights across different intervals.

2.2. Weighted Uniform Distribution

Weighted uniform distribution

The definition sounds complicated, but when you define it for a one-dimensional interval, you realize that it’s really quite simple.

- $S = [a,b]$

- $\mathcal{A} = \left\{[x_{i-1},x_i)\right\}_{i=1}^n$ and $\Delta x_i \equiv x_i - x_{i-1}$

- $\displaystyle \text{WUnif}(x|\mathbf{M}, \mathcal{A}) = \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j}\sum_i M_i 𝟙_{A_i}(x)$

Moving forward with our one-dimensional context, we’ll utilize this straightforward definition for our calculations. To begin, we can swiftly demonstrate that this function qualifies as a probability density function.

$$ \begin{aligned} \int_a^b \text{WUnif}(x|\mathbf{M}, \mathcal{A}) dx &= \int_a^b \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j}\sum_i M_i 𝟙_{A_i}(x) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j}\sum_i M_i \int_{a}^{b} 𝟙_{A_i}(x) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j}\sum_i M_i \cdot \Delta x_i \\ &= 1 \end{aligned} $$

Sampling from a weighted uniform distribution is indeed straightforward, and the process is as follows:

-

Choose one of the $n$ bins, where the probability of selecting a particular bin is proportional to its area, calculated as $\displaystyle \frac{M_i \cdot \Delta x_i}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j}$.

-

Once a bin is selected, generate a sample from the uniform distribution within that bin.

When Max Pooling is applied to determine the weights $\mathbf{M}$ and the set $\mathcal{A}$ (which includes the bins), and if the bin lengths are equal, the term $\Delta x_i$ cancels out. This simplifies the probability of choosing any bin to $M_i / \sum_{j}M_j$. This simplicity is a significant advantage when implementing the sampling algorithm, making the process computationally efficient.

2.3. Piecewise Rejection Sampling

The weighted uniform distribution, which we can readily sample from, is a viable choice for $g(x)$ in rejection sampling. But instead of selecting random weights and bin lengths, we will use Max Pooling to derive $\mathbf{M}$ and $\mathcal{A}$, ensuring that our $g(x)$ always remains above $f(x)$. This procedure is outlined in the following steps:

-

Determine the number of bins to segment the entire range into, denoted as $n$. Define $\mathcal{A}$ by splitting the interval into $n$ equal-length sections.

-

Perform Max Pooling on $f(x)$ across the established bins to ascertain $\mathbf{M}$, the set of maximum values within each bin.

-

Utilize $\mathbf{M}$ and $\mathcal{A}$ to construct a weighted uniform distribution.

-

Implement rejection sampling using this specifically defined weighted uniform distribution as $g(x)$.

This approach is aptly named Piecewise Rejection Sampling because it involves sampling within discrete bins. When you compute the acceptance rate for this method, it becomes clear that it can substantially improve the acceptance rate over using a simple uniform distribution for rejection sampling.

$$ \begin{aligned} P(U < f(Y)) &= \int_a^b P(U < f(Y) | Y = y) \cdot g(y) \, dy \\ &= \int_a^b P(U < f(y)) \cdot \text{WUnif}(y|\mathbf{M}, \mathcal{A}) \, dy \\ &= \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j} \sum_i M_i \int_{A_i} P(U < f(y)) dy \end{aligned} $$ Since $U \sim \text{Unif}(u|0, M_i)$ and $P(U < f(y)) = f(y)/{M_i}$, it can be simplified to: $$ \begin{aligned} P(U < f(Y)) &= \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j} \sum_i \int_{A_i} f(y)\, dy \\ &= \frac{1}{\sum_{j}M_j \cdot \Delta x_j} \geq \frac{1}{M_\max \cdot \sum_{j} \Delta x_j} = \frac{1}{M} \end{aligned} $$

The final part of the inequality references that the greatest value among the $M_i$ when multiplied by the total interval length is equal to $M$, aligning with the area under the curve of the original uniform distribution. This fact confirms that the acceptance rate for piecewise rejection sampling will always exceed that of a simple uniform distribution.

To tackle the initial problem we introduced, we’ll employ piecewise rejection sampling. The algorithm for this has been integrated into the Rust numerical library Peroxide, which we will utilize for our solution. Using this library streamlines the process, allowing us to efficiently apply the piecewise rejection sampling method we’ve outlined.

// Before running this code, you need to add peroxide in Cargo.toml

// `cargo add peroxide --features parquet`

use peroxide::fuga::*;

#[allow(non_snake_case)]

fn main() {

// Read parquet data file

let df = DataFrame::read_parquet("data/test.parquet").unwrap();

let E: Vec<f64> = df["E"].to_vec();

let dNdE: Vec<f64> = df["dNdE"].to_vec();

// Cubic hermite spline -> Make continuous f(x)

let cs = cubic_hermite_spline(&E, &dNdE, Quadratic);

let f = |x: f64| cs.eval(x);

// Piecewise rejection sampling

// * # samples = 10000

// * # bins = 100

// * tolerance = 1e-6

let E_sample = prs(f, 10000, (E[0], E[E.len()-1]), 100, 1e-6);

// Write parquet data file

let mut df = DataFrame::new(vec![]);

df.push("E", Series::new(E_sample));

df.write_parquet(

"data/prs.parquet",

CompressionOptions::Uncompressed

).unwrap();

}

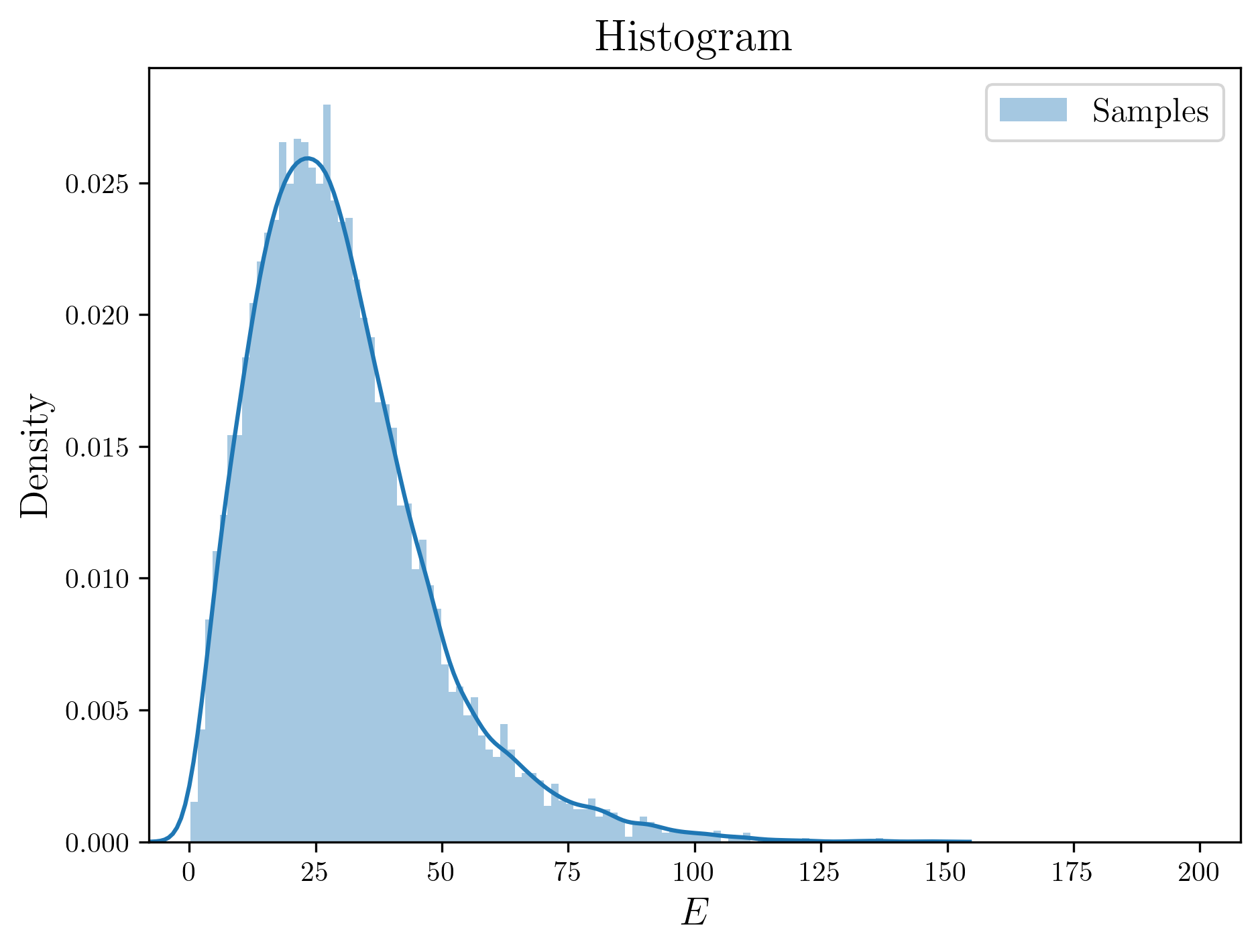

If you plot the data in a histogram, it looks like this:

Finally, we get samples!

References

-

Yen-Chi Chen, Lecture 4: Importance Sampling and Rejection Sampling, STAT/Q SCI 403: Introduction to Resampling Methods (2017)

-

Ovidiu Calin, Deep Learning Architectures: A Mathematical Approach, Springer (2020)

-

Tae-Geun Kim (Axect), Precise Machine Learning with Rust (2019)

A. Footnotes

[1]: The figure used here depicts the spectrum of Axion Like Particles (ALPs) emitted at a specific time from a Primordial Black Hole (PBH). You can find more details about this in this paper.

[2]: In this scenario, one could approximate the distribution’s nodes using cubic spline interpolation, calculate the cumulative distribution function via numerical or polynomial integration, and then obtain the inverse function through further interpolation. However, this method may yield inaccurate and inefficient results, which is why it’s not the recommended approach.